AMERICAN AND SPANISH SCIENTISTS PUBLISH THAT THE OLDEST SAPIENS IN EUROPE IS THE BANYOLES JAW (GIRONA)

An international team of researchers from Spain and the United States have just published a study, led by Binghamton University Anthropology and EvoS graduate student Brian Keeling, on an enigmatic fossil human mandible from the site of Banyoles in northeastern Spain.

Map of the Iberian Peninsula indicating the location where the Banyoles mandible (yellow star) was found along with Neandertal sites (orange triangles) and Homo sapiens sites (white squares).

The mandible was discovered during quarrying activities in 1887, and has been studied by different researchers over the past century. The Banyoles fossil likely dates to between approximately 45,000-65,000 years ago, at a time when Europe was occupied by Neandertals, and most researchers have generally linked it to this species.

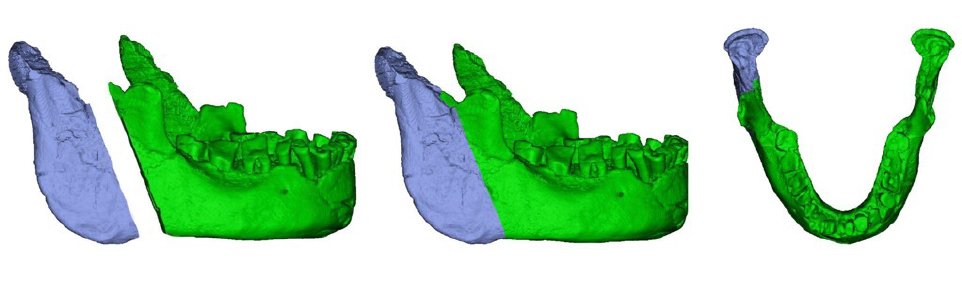

The new study relied on virtual techniques, including CT scanning of the original fossil. This was used to virtually reconstruct missing parts of the fossil, and then to generate a 3D model to be analyzed on the computer.

The authors studied the expressions of distinct features on the mandible from Banyoles that are different between our own species, Homo sapiens, and the Neandertals, our closest evolutionary cousins.

Reconstruction process of a 3D model of the Banyoles mandible. a) Right lateral view of the Banyoles mandible during the global alignment process. The red dots indicate pairs of landmarks used to align each piece of the mandible to each other. b) Right lateral view of the Banyoles mandible after reconstruction and global alignment. The blue, green, and red arrows indicate manual mode where the user manually moves each object together. c) Superior view (left) and right lateral view (right) of the Banyoles mandible after mirroring the right condyle. Highlighted piece in blue indicates a mirrored element.

The authors applied a methodology known as “three-dimensional Geometric Morphometrics” that analyzes the geometric properties of the bone’s shape. This makes it possible to directly compare the overall shape of Banyoles to Neandertals and H. sapiens.

Keeling stated: “Our results found something quite surprising, Banyoles shared no distinct Neandertal traits and did not overlap with Neandertals in its overall shape.”

While Banyoles seemed to fit better with Homo sapiens in both the expression of its individual features and its overall shape, many of these features are also shared with earlier human species, complicating an immediate assignment to Homo sapiens. In addition, Banyoles lacks one of the most diagnostic features of Homo sapiens mandibles, the presence of a chin.

Quam stated “We were confronted with results that were telling us Banyoles is not a Neandertal, but the fact that it does not have a chin made us think twice about assigning it to Homo sapiens. The presence of a chin has long been considered a hallmark of our own species.”

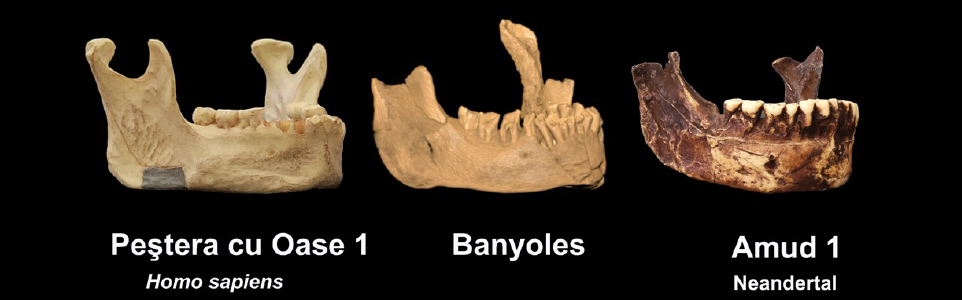

Side view comparison of mandibles between H. sapiens (left), Banyoles (center), and a Neandertal (right).

Given this, reaching a scientific consensus on what species Banyoles represents is a challenge. The authors also compared Banyoles with an early Homo sapiens mandible from a site called Peştera cu Oase in Romania. Unlike Banyoles, this mandible shows a full chin along with some Neandertal features, and an ancient DNA analysis has revealed this individual had a Neandertal ancestor 4-6 generations ago. Since the Banyoles mandible shared no distinct features with Neandertals, the researchers ruled out the possibility that Banyoles represented an admixture between Neandertals and H. sapiens.

The authors point out that some of the earliest Homo sapiens fossils from Africa, predating Banyoles by more than 100,000 years, do show less pronounced chins than in living populations.

Thus, these scientists developed two possibilities for what the Banyoles mandible may represent: a member of a previously unknown population of Homo sapiens that coexisted with the Neandertals, or a hybrid between a member of this Homo sapiens group and a non-Neandertal unidentified human species. However, at the time of Banyoles, the only fossils recovered from Europe are Neandertals, making this latter hypothesis less likely.

According to Keeling, “If Banyoles is really a member of our species, this prehistoric human would potentially represent the earliest H. sapiens ever documented in Europe.”

Whichever species this mandible belongs to, Banyoles is clearly not a Neandertal at a time when Neandertals were believed to be the sole occupants of Europe.

The authors conclude that “the present situation makes Banyoles a prime candidate for ancient DNA or proteomic analyses, which may shed additional light on its taxonomic affinities.”

The authors plan to make the CT scan and the 3D model of Banyoles available for other researchers to freely access and include in future comparative studies, promoting open access to fossil specimens and reproducibility of scientific studies.